In the mid-1990’s a 9,000-year-old skeleton was discovered in Kennewick, Washington. The finding triggered a massive cultural, political and scientific storm that would take two decades to dissipate. This was the now infamous Kennewick Man, one of the few human paleontological remains that might elicit recognition in the average person on the street, like the Australopithecus Lucy. Though the original reconstruction of Kennewick Man looked suspiciously like Patrick Stewart, Captain Jean-Luc Picard of Star Trek The Next Generation fame, the physical anthropologists working on the skull later concluded that Kennewick Man’s morphology was most similar to that of the Ainu, the indigenous people of Japan. But Kennewick Man was not fated to remain just a scientific curiosity. Controversy soon swirled over whether the native people of the region, like the Umatilla Indians, should have a veto over access to the remains as per the “Native American Grave Protection Act.” Bizarrely, Norse Neo-Pagans asserted a rival claim to Kennewick Man as an ancestor, due to the forensic reconstruction, which implied to them that this individual may have been related to European peoples. Though the debate died down over time, in 2015 DNA from the remains confirmed that Kennewick man was of Native-American genetic heritage. After this analysis was done, in 2017 he was finally reinterred, as per the wishes of the native tribes of the region.

For me, as a teen in the Pacific Northwest at the time, Kennewick Man was the only real North American archaeology story I was aware of. The news media loved it, reveling in the bizarre controversies and highlighting the numerous political and scientific conflicts, as well as the hijinks of the eccentric Neo-Pagans. What I did not know then was that away from the media circus, a revolution in our understanding of the origins and spread of humans across North America was coming to a simmer. A model called “Clovis First” was being overturned by new results, and awareness was dawning among paleoanthropologists that their longstanding framework no longer adequately explained the data coming in. By 2020, the generation-long transition from the old orthodoxy has finally been completed. We are now in a more nuanced, and yet still uncertain, understanding of the human arrival in North America.

Archaeology now tells us with a high degree of confidence that humans were in North America more than 20,000 years ago. And genetics now suggests those first peoples may not have been the ancestors of contemporary Native Americans. In the last few years, new data and methods have uncovered tantalizing and previously hidden strands of ancestry connecting tribes and ethnicities in the Amazon rainforest to the indigenous people of Australia and Papua New Guinea, ancestry totally lacking in modern indigenous North Americans or Siberians.

The Pleistocene Blitzkrieg

The Clovis First model was attractive because it was simple, elegant and explained much of the data. The arrival of modern humans at the end of the last Ice Age, around 13,000 years ago, coincided with the rapid extinction of many large land animals in the New World. It is at this time that human remains and artifacts begin to appear all over North America in significant numbers. Some sites appeared more ancient, but most researchers believed that there were problems with the radiometric estimates that produced those inconveniently older dates for them.

Archaeological sites associated with the Clovis Culture appear in the record 13,000 years ago. The view was that Siberian hunters crossed over from Eurasia to North America via Beringia, the “lost continent” subsequently inundated by sea-level rise after the melting of the ice sheets.

These Siberians brought with them spears with distinctive bifacial points, first discovered in Clovis, New Mexico, in 1929. They were big-game hunters, and in three hundred years, they expanded across the virgin territory of North America, which was rich in mammoths, bison, sloths and horses. Not coincidentally, these animals soon went extinct. They came, they hunted and they extirpated the native fauna, contrary to the recent stereotype of the continent’s indigenous people as natural-born conservationists.

Humans were an invasive species in the Clovis First framework. Their rapid sweep across the continent can be analogized to the spread of rabbits across Australia. North and South America were assumed to have been free of humans until the end of the last Ice Age, so megafauna presumably had no fear of the humans when they first arrived. And, just like the arrival of an invasive species, the massive human population growth fueled by seemingly unlimited resources in big game was followed by resource exhaustion, as the prey animals became scarce or went extinct, and the Clovis Culture disappeared. The collapse of the Clovis Culture then ushered in the numerous subsequent cultures and societies of North and South America.

There are many points where the Clovis First hypothesis still delivers insights. Early human remains in the New World only begin showing up around Clovis and after. The only DNA extracted from a Clovis site indicates that modern indigenous people in the New World share broad genetic similarities with the Clovis hunters. They are their descendants or at minimum descended from closely related early people. The Clovis people and modern Native Americans are both genetically branches of Siberians. When it comes to their archaeological impact, Clovis was like nothing else that came before in the New World. Their spears exhibited more craftsmanship and were produced in such large volume the wasted tips began to litter the landscape. And their skill at hunting seems to have had no parallel before in the New World, judging by the extinctions they precipitated. While ground sloths went extinct more than 10,000 years ago on mainland North America, they persisted for another 6,000 years on Cuba. It was the arrival of humans that triggered this island extinction.

But now, we know that the Clovis people were not the first humans in the New World. The earlier sites researchers have long had to explain away as dating mistakes, were probably not as it turns out aberrations, but the true legacies of long pre-Clovis human occupation.

Before Clovis

Sites older than Clovis have been under excavation for decades. But no human skeletons have been discovered much earlier than Clovis. The general consensus in the late 20th century was the ‘tools’ discovered at these locations might actually be dismissed as naturally occurring wear and tear generating flint flakes. But over time, the evidence that these locations were valid sites of human occupation that predated Clovis became difficult to rebut. Even though Clovis was indubitably a turning point in the impact of human habitation in North America, the scientific community now broadly agrees there must have been modern humans in North and South America before Clovis.

Oregon’s Paisley Caves show evidence of human occupation around ~15,000 years ago, thousands of years before Clovis. These caves have also yielded human coprolites: fossilized feces. In 2008, mitochondrial DNA, the maternal lineage, extracted from these coprolites at the site indicated genetic connections to Siberia and East Asia. Meanwhile, far to the south, in southern Chile, the Monte Verde site yielded grinding stones and burned charcoal that date to a similar era.

In 2002’s The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and Its Peoples archaeologist Tim Flannery admits that the Clovis First model was no longer tenable, but also acknowledges that since there wasn’t a replacement theory or model he was going to write much of the narrative as if it still held. But by 2021, too much evidence has accumulated for anyone to just pretend as if Clovis First is the only fully fleshed-out option. Paisley Caves and Monte Verde were already important sites twenty years ago which needed to be at least noted, but two new discoveries in 2020 and 2021 have further bolstered the inevitability of the conclusions they were pointing us to, sealing the fate of the hobbled old paradigm.

First, in 2020 the publication of results from Chiquihuite Cave in Central Mexico pushed back the human occupation of North America to at least 19,000 years ago (and perhaps 33,000 years ago). That team found nearly 2,000 primitive tools from an unknown culture at the site. In the year since the publication of the paper, the consensus among archaeologists has grown that this much earlier range is correct dating and so humans did indeed occupy the New World prior to 19,000 years ago. The Chiquihuite Cave does not just smash Clovis First, it is also far older than the more conservative dates in Paisley Caves and Monte Verde.

And now, in September of 2021, another publication confirms the very early human occupation of the New World. Ancient footprints in New Mexico have now been dated to 23,000 years ago, using carbon-dating of the plant detritus in corresponding soil layers. Archaeologists seem to agree that there is not much dispute that this is a solid finding. Carl Zimmer in The New York Times quotes archaeologist Ben Potter, who is skeptical of sites much older than Clovis in North America. Potter says, “I’d like to see stronger data, and I don’t know if it’s possible to get stronger data from this particular site...If it’s true, then it really has some profound implications.” This is a rather gentle objection, and for my money, points to the reality that these results are quite convincing on their face.

But archaeology is not the only discipline that’s been unsettling our previously tidy narrative of the origins of the native people of the New World: genetics has begun revealing strange connections to the populations of Australia and Papua New Guinea in South America in the last five years. Combined with archaeology, these wildly unexpected results open up unforeseen new possibilities, though without any tidy new successor certainties.

Out of Siberia

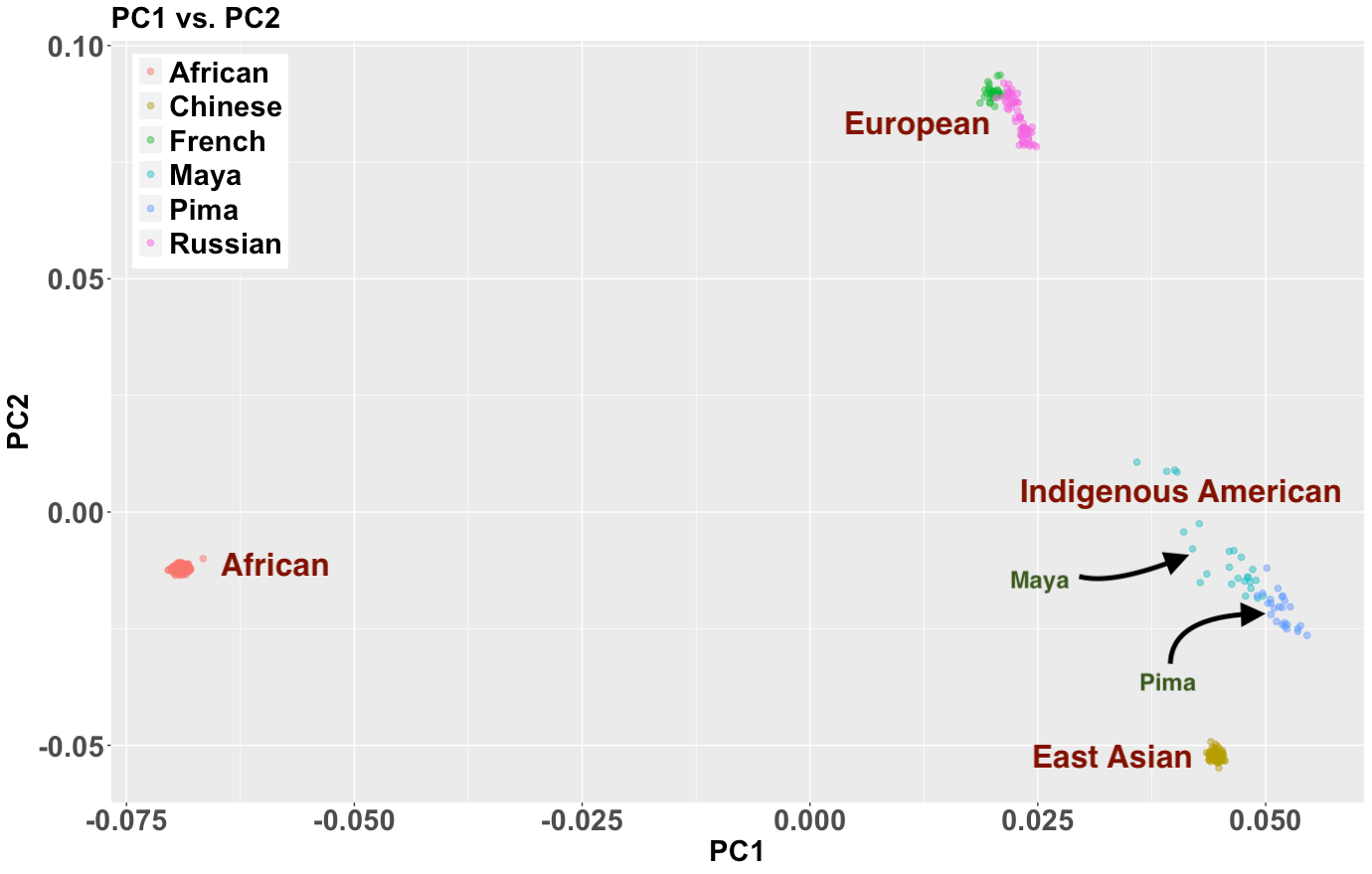

Despite the Australian genetic connections of some native peoples in the New World, physical anthropologists have long observed that the indigenous people of the New World are most similar to the populations of East Asia, in particular Siberia, when it comes to their morphology. All these populations have high frequencies of shovel-shaped incisors, as well as other characteristics like relative hairlessness and high cheekbones.

Genetics broadly confirms this pattern. The closest modern relatives of Native Americans are the peoples of eastern Siberia. And yet there have always been some stubborn wrinkles in this story. New World populations also show connections to Europeans, West Asians and South Asians on many genetic markers, while genetic-clustering algorithms find them shifted away from East Asians toward these other groups. The evidence from maternal and paternal lineages: the mtDNA and Y-chromosome respectively, is the clearest. Haplogroup X on the mtDNA is found across West Eurasia and in North America. More than 90% of the paternal lineages in the New World are haplogroup Q. Q is a “brother” lineage to haplogroup R, famously found from India to Ireland. The two main branches of R1: R1a and R1b are associated with Indo-Europeans, while R2 is mostly found in Iran and India. Q itself is also found in low but significant fractions across Central, West and South Asia, as well as Siberia.

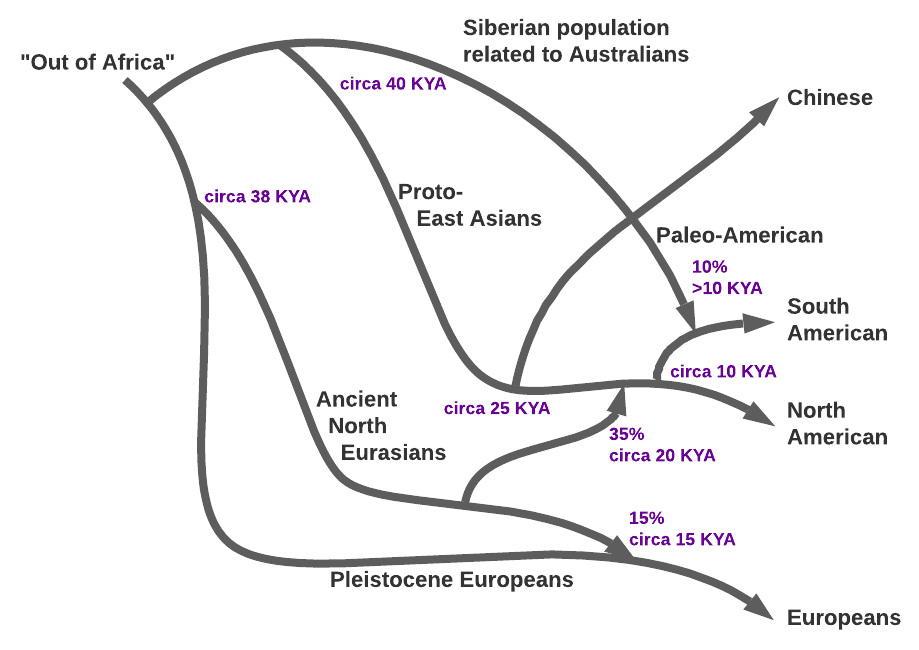

These patterns do not fit a neat model where Native Americans descend solely from the ancestors of modern East Asians. But we know now that the human family tree does not actually resemble a branching tree so much as a complex network anyway. In 2013, the DNA of a boy buried on the shores of Lake Baikal an estimated 24,000 years ago was analyzed using new techniques in paleogenetics ushered in by the sequencing of the Neanderthal three years earlier. Named for the site, he is known as the Mal'ta boy, and his overall genetic makeup is unlike any human alive today.

The distant Siberian ancestors of the Mal'ta boy separated from the last common ancestors of Europeans and West Asians some 38,000 years ago. But they were clearly of the same branch of ancestral humans that migrated north out of the Middle East 50,000 years ago, as opposed to those that swept eastward through India, and into East Asia and Australia. The population to which the Ma’ta boy belonged is called “Ancient North Eurasian” (ANE), and it left many descendents. ANE ancestry can be found across Europe, in West Asia and South Asia, as well as in some parts of East Asia and Siberia. But, perhaps the most surprising result was that 20-40% of the ancestry of modern Native Americans derives from the ANE. Meanwhile, 10-20% of the ancestry of Northern Europeans, from England to Russia, ultimately comes from the ANE, explaining the suggestive and mysterious connections between the two populations. The Mal’ta boy himself seemed to be Y-chromosomal haplogroup R, the ancestral lineage that exploded in the last 5,000 years with the Indo-Europeans (the prehistoric Yamnaya were 30-40% ANE in ancestry).

Subjecting ancient and modern DNA results to advanced computational models, we now see that the vast majority of the ancestry of contemporary Native Americans derives from an admixture between ANE tribes and early East-Asian Paleo-Siberians over 20,000 years ago. Out of the fusion of these two populations emerged the group that followed big game eastward, onto the tundra of Beringia, that vast subcontinent between North America and Siberia. Eventually, these ancient Native Americans moved southward as the ice sheets retreated, opening a path into the Americas proper, and brought with them the seeds of the catalytic Clovis Culture that would transform North America.

But that still leaves us with the question of who the earlier people were that left their footprints in New Mexico and tools in the caves of Mexico more than 20,000 years ago. They were a different kind altogether.

They come from a land down under?

Just as with the Mal'ta boy, it took new technology to uncover one of the most surprising, and still most mysterious, results to come out of New-World archaeology and genetics. Using much denser marker sets (hundreds of thousands as opposed to dozens of genetic variants) that allowed for exploration of statistical associations between hundreds of world populations, researchers uncovered a previously unidentified affinity between some native populations in the Amazon and the aboriginal peoples of Australia and Papua New Guinea. The lab had set up an open-ended model to compare populations against each other, and test for evidence of gene flow across them. In the vast majority of cases, the data charted no special connection. But to the researchers’ surprise, a few groups in the Amazon seemed to have gene flow from Australians and Papuans.

The sensational find of a connection between Oceanian populations that everyone believed diverged from the ancestors of Native Americans 50,000 years ago, and populations deep in the Amazon nearly 10,000 miles away, was greeted with skepticism, even internally within the lab. But the researchers checked and cross-checked the result for months, and it held. They concluded that earlier and more primitive techniques had simply not been powerful enough to pick up statistically robust signatures. It is hard to imagine Papuans or Australians migrating across the Pacific to South America. Rather, it seems likely that an ancient population more closely related to aboriginal Oceanians than to East Asians was present in Siberia more than 20,000 years ago. In 2018, ancient DNA from a skull in Brazil dated to more than 10,000 years ago also exhibited a detectable genetic connection to Australians and Papuans. Other remains from that period, including the DNA from the Clovis site, did not. This means that the Australian/Papuan-related population did not mix evenly into ancient indigenous populations, and may have arrived earlier and been absorbed.

In 2021, a consortium assembled DNA from indigenous people from the Pacific to the Atlantic in South America, compared the individuals to ancient and modern DNA from across the world, and discovered that low levels of Australian/Papuan-related ancestry were far more widespread than had earlier been thought. The faint affinity to Australo-Papuan populations extended across much of South America. They also found variation of the proportion of this ancestral component even within tribes, with some individuals carrying far more than others. This suggests that the admixture may have been relatively recent, and may not have been well-mixed across the population.

All of these genetic results were surprising, and do not fit neatly into the standard models and expectations. But what’s exciting is how they are perhaps less amazing now that archaeologists have confirmed that modern humans were almost certainly present in the New World 20-30,000 years ago.

Along the ocean’s shore

We are now beyond Clovis First, but the path forward is still unclear. The certainty that some humans were present in the New World before 20,000 years ago will require reevaluation of many sites whose findings were considered implausible. Archaeologists digging in Mexico will be working at Chiquihuite cave, discovered only in 2012.

And geneticists have also contributed novel results in the last few years. The people of the New World are relatively genetically homogeneous, likely due to the bottleneck of Beringia. The big game hunters who occupied Beringia between 20,000 to 15,000 years ago were clearly descended from known Siberian populations, and the vast majority of modern indigenous American ancestry derives from this stock. But now genetics also adds the twist that a small but detectable fraction of ancestry in South America comes from an unknown population distantly related to today’s aboriginal Australians and Papuans.

So with all this, are we equipped to say who the first Americans were? I think when all is said and done, we will find that the earliest humans in the New World were more closely related to the Australians and Papuans, rather than modern East Asians. In other words, the first modern humans who were present in the New World did not contribute much ancestry to today’s Native Americans at all. Only the ancestors of today’s indigenous South Americans genetically absorbed these earlier people who preceded the Beringians. This must have occurred more recently than 15,000 years ago when the Beringians arrived, and if the evidence for variation in ancestry in contemporary Amazonians is replicated, pockets of these earliest Americans may have persisted down to the relatively recent past.

The fact that we can say these people are related in some way to today’s Australians and Papuans draws our modern eyes to the tropical western Pacific. But it is more likely that these relatives of the Australo-Papuans were ancient Siberians. The world 30,000-40,000 years ago was different enough that we have to tread very carefully as we wend our way, mostly blindly, back to these forks in the family tree. The geographical connotations of modern terminology can mislead more than they illuminate. A great deal of circumstantial evidence indicates an ancient bifurcation between populations ancestral to modern East Asians and another group with closer connections to Australians. Today Y-chromosomal haplogroup D is found in Japan, Tibet, and the Andaman Islands. This is a clue to the likelihood of an ancient population in East Asia that was absorbed by expansionist millet and rice farmers widening their range outward over the last 10,000 years. The Australo-Papuan ancestry in modern indigenous South Americans likely derives from a northern branch of these long-lost ancient East Eurasians.

But how did these people arrive on the shores of America when vast ice sheets spanned North America and Siberia, blocking movement eastward? Long before the revolution in dating and genetics, archaeologists in the American West were developing a theory that the peopling of the New World could have occurred through a coastal migration. This model appeals because a fully ice-free corridor in the interior of North America does not seem to have opened up until 13,000 years ago when the Clovis people began to expand. Today the theory is necessary because it is quite clear modern humans arrived in North America more than 20,000 years ago, when we know glaciation blocked conventional landward migration out of Beringia into North America. So how does the theory run? The earliest Americans were related to a now-extinct group in coastal Siberia, distantly related to today’s Australo-Papuan populations. They were ocean-oriented and likely had small boats that they used to move along the shore. Many researchers believe that they exploited North-Pacific kelp forests, which can support maritime foragers. As they migrated eastward, they found isolated refugia surrounded by glaciated territory in western North America. Eventually, these earliest Americans arrived in America’s Pacific Northwest, south of the ice sheets, and settled in places like Oregon’s Paisley Caves.

The paucity of material remains, and the minimal impact on megafauna from these putative earliest arrivals leads us to suspect that these early humans existed at low population densities. The tools in Chiquihuite, Mexico are quite primitive and exhibit little change over time. Eventually, these earliest Americans moved southward and were the first occupants of the Monte Verde site in southern Chile. Here their population was larger, and the arrival of Beringians 13,000 years ago did not totally overwhelm them in the southern continent as it did in North America. Nevertheless, these unknown people who occupied the New World for nearly 10,000 years before the arrival of the ancestors of modern indigenous people remain like ghosts to us, leaving faint traces in the genetics of local populations, and only the most tenuous of material legacies. Their ecological footprint was light enough not only to allow for the flourishing of Pleistocene megafauna until the arrival of the Beringians, but it was also minimal enough that archaeologists denied their existence for decades, and geneticists failed to pick up their trace scent. But now? Both archaeologically and genetically, it’s a whole New World.