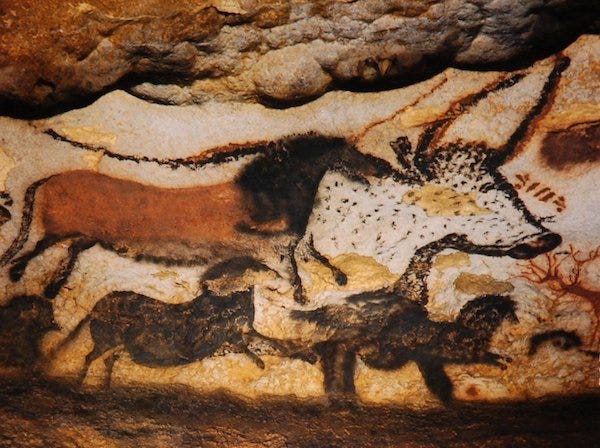

40,000 years ago the first modern humans arrived in Europe. They were the scions of a great scattering of Africans. One branch of the “Out of Africa” migration, from which the vast majority of the ancestry of modern peoples derive. These early modern humans were responsible for the cave paintings which are among the oldest works of art known from our species. Their cultural impact is powerful and has shaped our conceptions of the past for the past few centuries, as we’ve begun to develop an antiquarian interest as a species.

And yet it is notable that modern humans arrived in Europe thousands of years after they settled Australia. This, despite Europe being much closer to Africa than Australia as a simple matter of geography.

A straightforward explanation for the relatively late settlement of modern humans in Europe is that they were not the only humans present in Eurasia during their expansion out of Africa (in contrast to Australia, where placental mammals aside from bats were nearly nonexistent before the arrival of our species). Neanderthals had occupied the whole zone between the Atlantic and the Altai in a broad high latitude belt for hundreds of thousands of years, with their Denisovan cousins ranging further east.

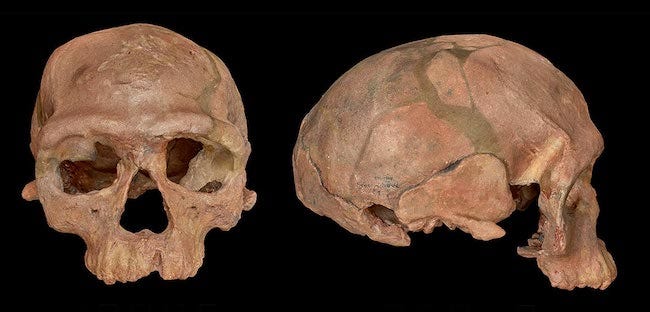

In the Near East, Neanderthals seem to have moved south during colder periods, as African-related humans retreated, with the dynamic reversing during warmer periods. Anatomically modern humans, people with more delicate skulls and flatter faces, had been present in Africa for hundreds of thousands of years while the Neanderthals flourished to their north.

But the coexistence was not to last.

Something different happened 40,000 years ago. A few thousand years after the arrival of modern humans in Europe, the Neanderthals disappeared from the fossil record. In the last decades of the 20th-century, the dominant view was that the Neanderthals had been marginalized or exterminated to extinction. They were an evolutionary dead-end, and the humans who arrived 40,000 years ago were the ancestors of modern Europeans.

But with DNA, ancient and not so ancient, the truth turns out to be more complex than we had imagined. In 2010 researchers in Germany discovered that the ancient genome of the Neanderthals had left an imprint in all the peoples outside of Africa. From Europe to Australia to the Americas. The conclusion is clear: our African ancestors mixed with Neanderthals somewhere in the Middle East before they spread out across the world.

Yet modern Europeans actually have less Neanderthal ancestry than people from eastern Asia, despite the fact that Neanderthals were residents of Europe for hundreds of thousands of years.

These strange facts tell us the deep human past was not a straightforward process of replacement and settlement, but probably involved multiple migrations and mixtures. When the first genome of a 40,000-year-old modern human European was sequenced, the results surprised many people.

The remains were from Peştera cu Oase, in Romania. The individual was from an early Aurignacian culture. This is the first archaeological tradition in Europe associated with modern humans. The two primary genetic findings from the individual who died at Peştera cu Oase is that they do not seem to have left any descendants among modern Europeans, and, they had considerably more Neanderthal ancestry than modern Europeans.

In fact, this particular individual had a recent Neanderthal ancestor four to six generations earlier!

So the earliest modern humans in Europe mixed with local Neanderthals, but also seem to have left no descendants today.

Because of Europe’s historical support for archaeological research, and the reality that the cool climate is optimal for preservation of remains and artifacts, the European Upper Paleolithic is well defined by many cultures with familiar names. Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean, and Magdalenian. These are just a few of the cultures which are well known to us from copious remains and objects.

These societies have served as the basis of popular cultural representations, from the Aurignacian people in The Clan of the Cave Bear to the Magdalenian tribe depicted in the 2018 film Alpha. If the Neanderthals represent one source of the archetype for “cavemen”, then these Ice Age European cultures represent another.

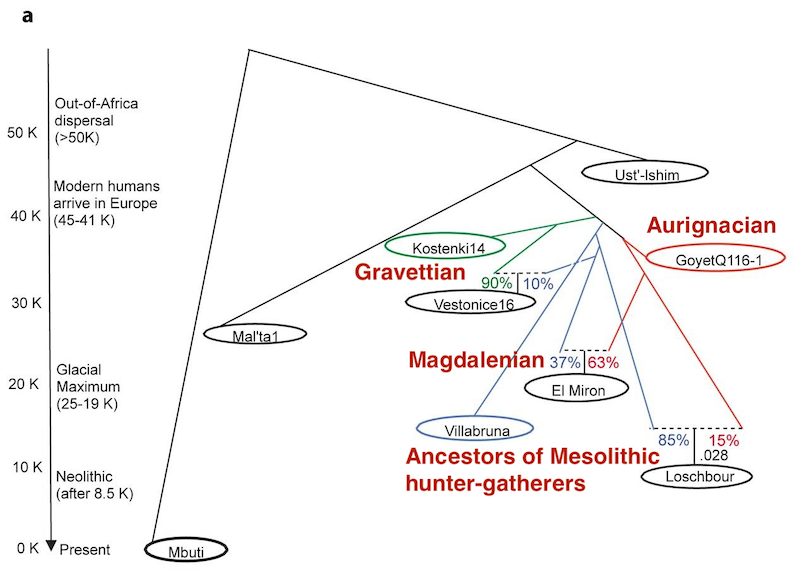

Now, over the past decade, geneticists have assembled a European temporal transect of samples from the period between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago. The whole period of the Upper Paleolithic occupation of Europe by modern humans. What they have confirmed is that Pleistocene Europe was defined by population turnovers and mixtures, which reshaped Europe’s genetic landscape several times across the Ice Age. This was not a static time, but a dynamic one.

The European hunter-gatherers who were indigenous to the continent when farmers arrived from the Near East with the Neolithic Revolution were themselves relatively recent arrivals, expanding only after the Last Glacial Maximum.

Though only a small proportion of the ancestry of modern Europeans seems to date to these Pleistocene peoples, the ancestry of later Aurignacian cultures, as well as the Gravettian, Magdalenian, archaeological complexes, has left an impact on modern Europeans.

The demographic history of Europe has been characterized by several repeated pulses of migration from the southeast and east. The earliest Aurignacians were replaced in totality, but the later ones seem to have been absorbed into the Gravettians, and also persisted in pockets across Western Europe, only to reemerge as one of the primary ancestral groups for the Magdalenian people. After the end of the Last Glacial Maximum, a final group of Pleistocene hunter-gatherers emigrated out of the fringes of Southeast Europe, the Near East, and the Caucasus, and assimilated the remnants of these earlier cultures.

It was this last wave of hunter-gatherers who eventually gave rise to the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers of Europe and also contributed to the ancestry of the first farmers in Anatolia, the Levant, and the Zagros.

The peoples of Ice Age Europe have left art which fascinates us to this day. Their efflorescence of creativity was such that the idea of “behavioral modernity” and the cognitive “great leap forward” arose to explain the new genius of our species. Now genetics now tells us that these early Europeans, who occupied the content for 30,000 years before the end of the Ice Age, left only a shadowy and faint imprint on present generations. In that way, they share a fate with the Neanderthals.

But the artistic legacy is something that will persist, haunting our imaginations. Though they may not be the ancestors of modern Europeans in a literal genealogical sense, through their works the influence of Pleistocene Europeans has persisted across the eons, and will continue to do so.

Echoes of Europe’s Pleistocene Past was originally published in Insitome on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.